Matthew Bell, 20 January 2025

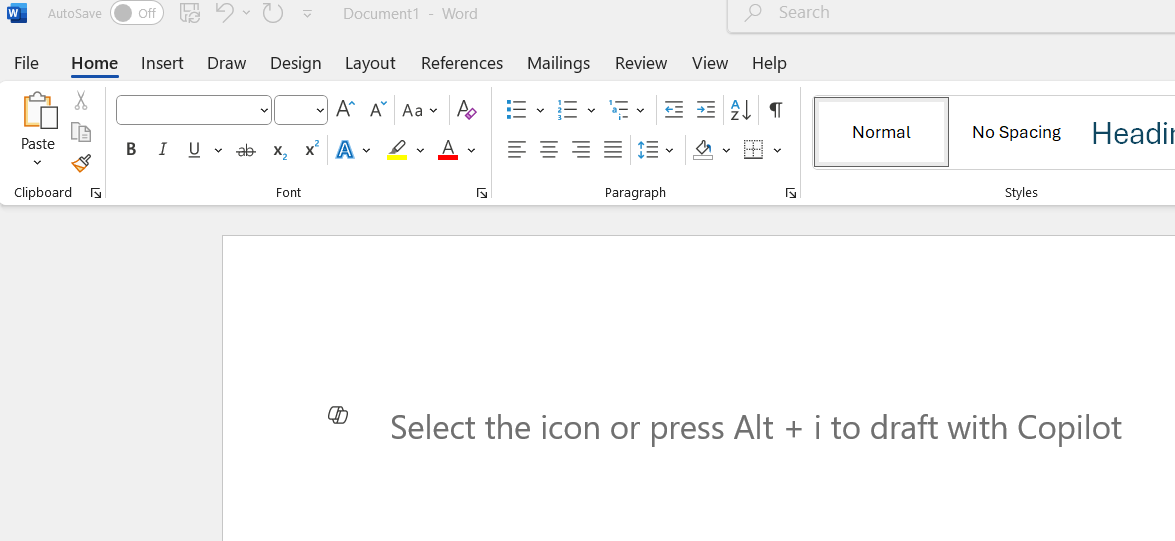

I can’t resist opening this reflection by going meta and relating an experience I had just as I began to write my first draft. I begin almost anything by first locating where in my filesystem I wish to save my creation; I then click the button labeled  , usually on the upper left-hand side of my window on my Windows 11 laptop. This gives me several options, say to create a new folder or a new Word document. That’s the option I took today as I set out to start a conversation on a strategy for inviting students to be collaboratively circumspect on where, when, and how they use AI tools to write, well, anything! Lo and behold, what was the very first response Microsoft Word gave as it jubilantly booted to life?

, usually on the upper left-hand side of my window on my Windows 11 laptop. This gives me several options, say to create a new folder or a new Word document. That’s the option I took today as I set out to start a conversation on a strategy for inviting students to be collaboratively circumspect on where, when, and how they use AI tools to write, well, anything! Lo and behold, what was the very first response Microsoft Word gave as it jubilantly booted to life?

Yes, you read that right: Word immediately pushed me to use Copilot to begin my draft before I had written a single character.i

This is the world we now ask our students to learn in. We assign them to write code or articles or posters or art or music as stages in a larger process of discovering themselves vocationally in the world. We also orient them to tools to enable that discovery. Tools, however, are not neutral. As the proverb goes, if you only have a hammer then you will try to use that hammer to do everything – even and hilariously for tasks to which hammers are not suited. Tools are intrinsically biased to optimize specialized tasks in particular contexts. I do not invoke the category of “bias” here pejoratively. Bias is not prejudice. The postmoderns are surely right when they say that everyone and everything operates with bias. This is no more intrinsically bad than a hammer. However, it does mean that we need to be circumspect and critical in our choice of tools. For the purposes of this article, I want to argue – heuristically and hopefully charitably – that the spirit of the age is short-circuiting the development of those powers of circumspection and criticism. We, as teachers, need to pursue countercultural strategies for rewiring our education systems and our students – and, frankly, ourselves as we research and write – to rediscover our shared, critical powers for reflective creation.

I’ll start with a couple more observations.

The context of this blogpost’s publication is Whitworth University, a Christian university. Also, my own background skillset is schizophrenically interdisciplinary, combining computer science with theology.ii So, my method in approaching this conversation will be to take a page from Christianity’s pastoral-theological (and missiological) playbook. Since the goal is to engender a countercultural response within the AI revolution, I’ll set my imagination to explore free-range on how Christianity, at a critical point of threat and decay in late ancient culture, set out to be generatively countercultural, interestingly in ways that arguably recreated culture.

That moment was the constitution of religious orders with rules of life.

For again heuristic and not dogmatic purposes – I’m letting my imagination run free range, after all! – here’s the quick and dirty history of that chapter, shamelessly highlighting precisely why I think there might be some surprisingly low-hanging fruit there for considering what to do at the Dawn of the AIs. In the 3rd century C.E. Christianity suffered one its most traumatic corporate experiences, the Diocletian persecution. Up to this point, Rome had actually been fairly tolerant of the new religion, but Ceasar wasn’t having it anymore. A systematic pogrom swept the Roman Empire. Coincidentally, the Empire also faced economic and political stressors that resulted in resentments between, e.g. its Egyptian province and the Imperial HQ. This had a curious result. His Majesty commanded that the Christians be publicly and gruesomely executed in settings designed as entertainment for the crowds. However, martyrs are kind of badass.iii When the masses – people who increasingly felt oppressed by their version of the 1% – saw Christians singing hymns or otherwise going stoically or even joyfully to deaths orchestrated by the very people those masses resented, large numbers of them began to convert. Diocletian’s strategies for seeking Imperial cultural unity backfired terribly. His now even more destabilized empire was ripe for picking by Constantine the Great, who promptly issued the Edict of Milan decreeing toleration for Christianity. Over the decades that followed Christianity’s star in the West rose higher and higher, from toleration to imperial favor.

This complex, organic political development created a bit of a crisis for the Faith. First, it now found its numbers gorged with enthusiastic converts, both from the conversions that the Diocletian persecution ironically produced and from converts entering the suddenly powerful religion because it was now politically favored. Second, its social status had changed overnight from being a countercultural movement to being chaplain to state and society! It’s intuitive to see how to follow, say, the “Sermon on the Mount” (Matthew 5—7) if you are under threat of martyrdom or some other form of cultural oppression. It’s not so easy to see that when you are now rapidly becoming the majority and when the Emperor is giving civic offices to your clergy and funding your churches. Enter St. Anthony of the Desert. He heard a sermon one day on Jesus’ call to give up everything. Tony decided to take that literally and begin a spiritual experiment in the desert regions of Egypt. In ways that evoke for me thoughts both of John the Baptist and Carl Jung, Anthony liquidated his substantial family assets, moved to the middle of nowhere, and faced down demons. And it worked. Tony developed a reputation for being a powerful exorcist, thaumaturge, and holy man. This impressed the eccentric and extroverted bishop St. Athanasius to write Tony’s biography, which then became a best seller. Spiritually and existentially hungry folk, people longing for depth in an age of banality and increasing anxiety, began to read it and get ideas. However, Anthony’s lifestyle proved too extreme for a great many of his admirers and their efforts at imitating him ended in predictable disaster. Clearly, St. Tony was on to something, but scaffolding was needed.

Enter religious orders. The idea was elegantly simple. Someone with the graced discipline of a Tony would make him/herself available to a community of siblings to learn the spiritual life.iii That father would then organize the community around a compendium of practical spiritual guidance that would serve as a rule of life.iv That rule bound those who lived in the community voluntarily to practices that were, in turn, designed to initiate to bedrock spiritual reality and to reinforce solid habits. There was the scaffolding! The results were a paradigm setting success, but that’s maybe a story for a different blogpost.v

That is the page I’d like to consider taking from Christianity’s playbook.

Here’s the intuition: our students find themselves in a rapidly mutating culture, one where the pace of change, much of it wrought by technological advance, verges on the terrifying, and which at points threatens a tsunami of banality. Those changes render the embrace of graced discipline intrinsically hard: the tools we must learn to use in this rapidly changing global economy are biased in ways that simultaneously occlude human powers of self-differentiation, critical thinking, and reflective creation and design. All this is occurring at a stage of heightened anxiety, especially on economic and political themes, producing graduating high school seniors whose capacity to respond in healthy ways to stress is enervated and even anemic.vi Scaffolding is needed to promote healthy use and further innovation of AI tools in our setting, a pattern of health that increasingly looks countercultural. This picture looks eerily like that wherein Christianity found itself in the late ancient world. Might we invite students and faculty into patterns of community where we voluntarily bind ourselves to practice disciplined use of AI (specifically) and technology (generally) precisely so that we might continue its innovation? If so what “rule of life” might express those voluntarily agreed upon community disciplines?

What might such a community rule involve? Here, I’ll depart from history a bit and propose some touchstones to be explored in further conversation (or possibly expanded upon in a later blogpost).

- Whitworth University already has a student handbook with academic honesty policy. That policy is expanded upon in several departments. The proposed rule should be distinct from that AH policy because its purpose is different, albeit related. The rule should express a voluntarily embraced, positive and generative communal exercise of discipline under direction. (By contrast, the AH policy is a prohibition of unethical behavior – not the same thing!)

- The rule should not be a class or a syllabus. It should express a shared habit of life applying to anyone within our community of scholars who embrace it, and it should be applicable both inside and outside the classroom.

- The rule should begin with and cohere with a clear goal stated at an appropriate level of abstraction. For example, the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola has a longer title that succinctly expresses its whole goal: “Spiritual exercises to conquer oneself and regulate one’s life without determining oneself through any tendency that is disordered.”vii For this rule, a good purpose statement might be: “The purpose of this Rule is to empower us to direct these developmental years in our lives unto the ends of becoming competent and ethical innovators and servant-leaders in an increasingly bored and anxious world.”

- To keep rules of life actionably succinct, some present-day riffs on them organize their practices into two sections: vital practices and regular habits.viii Vital practices describe the core, day-in-day-out must-dos that promote healthy living and, because they are so centrally important, are kept to a minimum. Regular habits can be more expansive and are built upon the vital practices. An example vital practice in this context might be, “Journal weekly on how I am using, and learning to use, the tools I need to learn and create, and check in twice a semester with my advisor on that ongoing experience.” A regular habit might be to read an article or two per semester on the perils and promise of using ChatGPT and other AI tools.

- Rules of life really don’t work without authentic community and were originally designed to be practiced with mentors (“fathers”) as well as peers. This rule needs to be written with this in mind, setting down practices and expectations for professors no less than for students! The core expectation about the professor is that s/he function as a mentor in a process of discernment and discovery, ready to ask hard questions and to provide humble, informed guidance.

Obviously, the above envisions but does not yet specify a rule. Perhaps that should await a further blogpost.

Endnotes

- Word’s response was even more striking than that. This was the first time I was using Office365 since my installation had auto updated to prefer use of Copilot. A pop-up enthusiastically took over my screen telling me about its emergent mutant AI superpowers. It then asked me to try out Copilot to write my article. Further, as I typed, Word kept on annoyingly populating the left hand of my screen with the Copilot icon, making it hard not to click it given its prominent location! The whole user interface was designed to steer me towards using Copilot, even to the point of making it hard not to and even when doing so made little sense.

- Relevantly, my computer science background focused on computational corpus linguistics and natural language processing, research that dreamed up and made use of ever larger language models. My work in historical theology is adjacent to observing when and how Christianity gave rise to religious orders. Spoiler alert!

- I draft this on January 20, Dr. Martin Luther King Day. I cannot help but pause to write this footnote to one such awe-inspiring martyr.

- Two such persons were St. Benedict of Nursia and St. Augustine of Hippo. On a different note, my use of the term graced discipline is owed to a modern-day Tony of sorts, Richard Foster, who popularized the term in his Celebration of Discipline.

- The words commonly used for the fatherly role in the community, abbot / abbess, draw from the Hebrew root word Abba (meaning that an abbess is a woman father!). The term “rule” relates to the Latin regula (Greek Kanon) and originally signified an architectural design tool, the measuring rod. Christians used the term metaphorically to describe the sort of role played within the Faith by, e.g., the Bible itself, namely as a means of “measuring” faith and vocational ethics. However, it may be that the metaphor had hardened and grown opaque by the time the first rules of life were being drafted.

- This insight was suggested to me by Pete Tucker (Math and CS Department, Whitworth) in an email where he provided some advance critique of the proposal I am making here: “[S]tudents generally seem far less equipped to handle stress as compared to students even 5 years ago. (Can I blame COVID?)” Peter Tucker, personal email correspondence, 12 December 2024.

- St. Ignatius of Loyola, The Spiritual Exercises. I have used Fr. Mullen’s accessible translation originally published by P.J. Kenedy and Sons: New York, 1914. This translation was made available by the Christian Classics Ethereal Library online at https://ccel.org/ccel/ignatius/exercises/exercises. Last accessed 20 January 2025.

- I obtained this model from the Rev. Dr. Alyssa Bell, who is also a spiritual director in the Spokane area and a senior adjunct for the School of Continuing Studies. I also happen to be married to her.